So here goes.

1. Let the Right One In and The Signal (both 2008)

Directed by Tomas Alfredson (Right One) and David Bruckner, Dan Bush, and Jacob Gentry (Signal)

2008 reignited my passion for horror movies after a slow, nearly decade-long falling out with the genre, and it was these two films -- wildly different but each brilliant in its own way -- that did it.

I saw The Signal first, and I walked away convinced I wouldn't see a better horror film for at least another decade. Conceived by a collective of independent Atlanta filmmakers working with prosumer equipment, the movie is told in three elegantly interlocking parts, each written and directed by a different person but all forming a cohesive -- if utterly demented -- whole. The story is deceptively simple: a strange electronic signal delivered through TVS, radios and cell phones turns all of the denizens of a fictional American city into homicidal maniacs. I don't want to say anything more about it for fear of spoiling the experience. Just trust me when I say this is the most original and thought-provoking American horror film in years. And it was all done for a budget of about $200,000.

So when I saw Let the Right One In some months later, I was stunned to discover that it was even better. Austere, chilly and deliberate where Signal is heated and frenetic, Right One manages to do what Twilight, True Blood, Thirst, Underworld, and all the other "vampire chic" movies and TV shows in recent years have so far failed to do ... make vampires scary again. The swimming pool scene toward the end is worth the rental price alone.

2. The Business of Fancydancing (2002) and Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001)

Directed by Sherman Alexie (Fancydancing) and Zacharias Kunuk (Atanarjuat)

NOT SAFE FOR WORK!!!

I don't really like the term "indigenous film" because it smacks to me of white liberal condescension, but I think it's worth noting that two of the best independent films from the early part of the decade came from Native American (or Canadian) filmmakers using the then new medium of digital video.

Fancydancing was written and directed by novelist/poet/screenwriter Sherman Alexie, and it follows Seymour Polotkin (Evan Adams), a gay Native American poet living in Seattle, as he returns home to the reservation he grew up on to attend a childhood friend's funeral. The film comes off as one part documentary, one part traditional narrative, and one part visual poem. It will creep under your skin without you even knowing it, and the quiet but crushing ending can reduce even the most macho dude to tears (trust me, I've seen it happen).

Atanarjuat is a very different film. Written and acted entirely in Inuktitut, it is the cinematic realization of a centuries old Inuit myth about the title character. Director Zacharias Kunuk provides almost no narrative context for non-Inuit audiences, choosing instead to toss us head-first into the story, and he uses the DV format to lend the film a sense of both immediacy and reality. The result is a movie that feels in some ways like a Maysles brothers documentary. Yet Kunuk still manages to create a stunning visual landscape, wringing images out of his video camera that a studio cinematographer would envy. It's a long movie, and slow going, but well worth it.

3. Michael Clayton (2007)

Written and directed by Tony Gilroy

The directorial debut from screenwriter Tony Gilroy (Dolores Claiborne, The Devil's Advocate, the Bourne trilogy, among others), Michael Clayton was sort of lost in the shuffle during a powerhouse year that offered up such lauded (and I would argue overrated) films as No Country For Old Men and There Will Be Blood. Critics had nice things to say about it, but audiences didn't really notice and all the available Oscar buzz got sucked up by the Country/Blood showdown.

Granted, a legal thriller about a cynical lawyer (George Clooney) confronting the depths of corporate greed is familiar terrain oft-traversed by the likes of John Grisham and Scott Turrow. But that's selling this movie short. Michael Clayton is oh-so-much better than its legal-thriller genre origins would suggest. Click on that clip I posted above, close your eyes and listen to Tom Wilkinson's opening monologue, and try to tell me that this isn't the work of an A-list screenwriter operating at the absolute top of his game. Michael Clayton is the type of straightforward movie that Hollywood does best, when it can get its shit together.

4. Shaun of the Dead (2004)

Directed by Edgar Wright

This is the movie that singlehandedly destroyed my beloved zombie subgenre and forever dashed my aspirations of making a truly scary, super-serious zombie movie like the ones I grew up on. After receiving the Edgar Wright/Simon Pegg treatment, I just don't think zombies can ever be taken seriously again.

But that's okay, because this movie is so friggin' awesome I can't be mad at it. Smart, silly, and -- yes -- even scary at times, Shaun of the Dead injected a much-needed shot of comedic tough love into an admittedly (begrudgingly, on my part) tired formula. The film transcended parody and proudly entered the pantheon of great horror comedies, unceremoniously batting Return of the Living Dead aside like a rag doll and knocking An American Werewolf in London off its long-occupied throne. And we all must now bow before it.

5. Memento (2000)

Written and directed by Christopher Nolan

The backwards-unfolding structure of this movie could have been a hopelessly irritating gimmick, but writer/director Christopher Nolan used it to craft a brilliant exploration of the very nature of memory and identity. And he managed to make a pretty awesome neo-noir thriller as well. Memento is now considered an undisputed classic, and it's as stunning to me these days as it was when I first saw it almost ten years ago in the theater. If you haven't seen it in awhile, go back and give it another watch. I promise you'll see things you missed the first time around.

Plus, it has Joey Pants. You can never have enough Joey Pants in your life.

6. Little Children (2006) and House of Sand and Fog (2003)

Directed by Todd Field (Children) and Vadim Perelman (House)

I grouped these two films together because of the presence of the generally amazing Jennifer Connelly, but it says something when you stop and realize that hers isn't the strongest performance in either film.

Little Children, directed by Todd Field (In The Bedroom) and adapted from a novel by Tom Perrotta (Election), was criminally unappreciated upon its release. A seemingly familiar tale of suburban infidelity, it's both funny and tragic, deleriously sexy, and is wonderfully acted from start to finish. It reintroduced us all to Jackie Earle Haley, whose turn as pedophile Ronnie James McGorvey is so alternately creepy and heartbreaking that it will leave you breathless, near tears and desperately wanting a shower. And Kate Winslet's pretty good, too.

House of Sand and Fog is probably the better film (although I'm partial to Children). Connelly and Ben Kingsley soar as two broken people battling each other and their personal demons in a tug-of-war over a repossessed house. There's nothing funny about this one, and the conclusion left me shaking in my seat. This is a movie that cuts to the bone.

7. Zodiac (2007)

Directed by David Fincher

David Fincher fans expecting another violent bruiser like Se7en or Fight Club were largely disappointed by the slow-paced, talky, and necessarily open-ended Zodiac. What they failed to realize was that this is a mature film for grownups, and it's less a serial killer movie than an old-fashioned, 1970s-style newspaper movie. Granted, I was predisposed to like it because of my already established fascination with the Zodiac Killer (which came from reading the book by Robert Graysmith, who's portrayed in the movie by Jake Gyllenhaal), but I still fly in the face of movie-geek wisdom by maintaining that it's Fincher's best. And, besides, it comes with my favorite movie soundtrack since Natural Born Killers.

8. Brokeback Mountain (2005)

Directed by Ang Lee

I almost didn't post this trailer, since it -- along with the theme song and the "I wish I knew how to quit you" line -- have been reduced to an unfortunate parodic shorthand in the years since. But watching it just now reminded me how much I love this movie, which for my money is one of the most starkly effective works of cinema I've seen. Masterfully directed by Ang Lee (robbed at the Oscars by that hack Paul Haggis) and adapted from an Annie Proulx short story by veteran writer Larry McMurtry (along with writing partner Diana Ossana and frequent Lee collaborator James Schamus), this is the movie that reminded all of us that Heath Ledger could act. He may now be forever remembered as the Joker, but this is the performance that stole my heart (and I'll thank you to stop your snickering).

9. Grizzly Man (2005) and The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009)

Both directed by Werner Herzog

Werner Herzog has proven to be one of the most fascinating documenters of human folly and psychosis that cinema has to offer (this probably comes from all that time he spent hanging out with Klaus Kinski back in the 70s). In his documentary Grizzly Man, he focuses on a real-life crazy person: Timothy Treadwell, a failed actor who got it into his head to go to Alaska and hang out with a bunch of hungry grizzly bears all summer without any means to defend himself. He did this for years, proclaiming over and over again that he would die for his beloved bears. And then one of his beloved bears decided to eat him, along with (sadly) his girlfriend, who Treadwell drug along with him on his delusional adventure almost against her will. Herzog mixes Treadwell's footage with interviews and his own acerbic commentary, and he presents a vision of this story that is both funny and tragic, occasionally sympathetic and at times downright cruel. In true Herzogian fashion, we can't help but think the celebrated German filmmaker is reveling a bit in the tawdry details of the story. And who can blame him?

If you doubt that, then look no further than his latest...er...opus, The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans. Ostensibly a remake of Abel Ferrera's...um...classic indie from the early 90s, Bad Lieutenant is nothing BUT tawdry details. I'm not sure I can really defend this choice as one of the best films of the decade, but I will say that I had more fun with it than almost anything else I've seen in the last ten years and it's so gloriously, stupendously demented that I couldn't not mention it here. Nicolas Cage is far from my favorite actor, but what he does in this movie is simply mind-blowing. It really has to be seen to be believed.

10. A History of Violence (2005)

Directed by David Cronenberg

I really tried not to overfill this list with dude-oriented movies about sex and violence, but what can I say? I like what I like. That said, as movies about sex and violence go, David Cronenberg's adaptation of the graphic novel by John Wagner and Vince Locke is curiously flat in the depiction of both. That's because Cronenberg has spent a career working his way through weirdo, existential horror movies on an endless quest to explore the frayed edges reality and examine the ways humans find to create their own reality. Violence isn't really about violence at all, but rather about how a man can -- through sheer force of will -- become someone else entirely. Cronenberg and Violence star Viggo Mortensen explored similar thematic territory with their somewhat less effective followup, Eastern Promises. That was a good enough movie, but I think Cronenberg really said all he needed to say on the subject with this one.

11. Infernal Affairs (2002) and The Departed (2006)

Directed by Andrew Lau and Alan Mak (Affairs) and Martin Scorsese (Departed)

I can't get away from this list without mentioning Andrew Lau and Alan Mak's Hong Kong crime thriller Infernal Affairs and its American, Scorsese-helmed remake The Departed.

It's unfashionable to say one prefers The Departed to Infernal Affairs, and it's true that Departed is sprawling and messy next to the cold elegance of Lau and Mak's original. It's also true that Departed is seriously marred by a "what-the-fuck?" performance by an eternally phoning-it-in Jack Nicholson. But, after living in Boston for a couple years and having subsequently become obsessed with the real-life tale of Boston gangster Whitey Bulger, around which Scorsese and screenwriter William Monahan refashioned their story, I have to say I prefer The Departed. The film captures the language, feel, and texture of Boston in a way that no other film I've seen has before it (take THAT, Mystic River), and -- Nicholson aside -- the performances are nearly pitch perfect across the board. Even Vera Farmiga shines in a role that by rights should never have been written.

Is it crazy to think of The Departed as the final part of a trilogy, preceeded by Goodfellas (1990) and Casino (1995)? I think not.

12. In Bruges (2008)

Written and directed by Martin McDonagh

NOT SAFE FOR WORK!!!

I'm not going to say a whole lot about this one. If you watched the clip above you get the idea. In truth, Martin McDonagh is a brilliant playwrite -- nasty, profane, and funny, sure, but with a surprising capacity for spiritual depth and a truly genius touch with character -- and In Bruges is a startlingly solid first step into feature filmmaking (his Oscar-winning short, Six Shooter, is even better). Watch out for him in the future.

13. This Is England (2006)

Written and directed by Shane Meadows

I've mentioned this movie and talked about Meadows before, so I'll try not to dwell. Meadows is one of the most exciting filmmakers working in England today, and his semi-autobiographical film about the rise of the at-first benign skinhead movement and its corruption by the racist National Front is as eye-opening as it is entertaining. Thomas Turgoose is a firecracker as the young lead, Shaun, and Stephen Graham is absolutely chilling as Combo, Shaun's vicious mentor in the ways of English nationalism. This Is England is like a rich, raw wound needing to be bled.

*****

There are a lot more movies I'd like to talk about, but this post is already ridiculously long so I'll just give a quick shoutout, in no particular order, to:

The Last King of Scotland

American Psycho

Dancer in the Dark

Ginger Snaps

High Fidelity

Requiem for a Dream

Traffic

Ghost World

Waking Life

Adaptation

City of God

Spider

Amores Perros

Battle Royale

21 Grams

Cabin Fever

Dogville

Elephant

Kill Bill Vol. 1 and 2

Love Actually

The Station Agent

Willard

Swimming Pool

Wonderland

Session 9

Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy

The Royal Tenenbaums

Sideways

Monster

The 40-Year-Old Virgin

Brick

Caché

The Constant Gardener

Dog Soldiers

Inside Deep Throat

Jarhead

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang

Land of the Dead

Match Point

The Proposition

Six Shooter

War of the Worlds

Wolf Creek

The Assassination of Richard Nixon

Before Sunset

Collateral

Dawn of the Dead

Downfall

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

Hotel Rwanda

The Lost

United 93

Clerks II

The Prestige

Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan

Volver

Stranger Than Fiction

Blood Diamond

Children of Men

Pan's Labyrinth

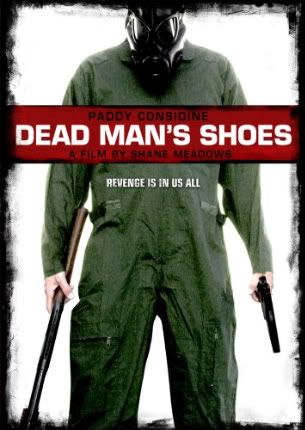

Dead Man's Shoes

An Inconvenient Truth

The Science of Sleep

The Lookout

Death Proof

Sunshine

Death Sentence

Eastern Promises

No Country For Old Men

Beowulf

The Mist

Juno

There Will Be Blood

Cloverfield

The Ruins

WALL-E

The Dark Knight

Burn After Reading

Milk

The Wrestler

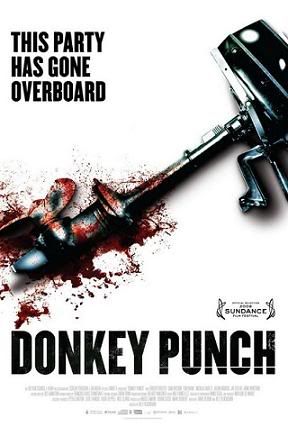

Donkey Punch

Coraline

Gomorrah

State of Play

District 9

Inglourious Basterds

Zombieland

Brothers

Avatar (sorry, Gene)

No End In Sight

Waltz With Bashir

Narc

Hard Candy