Seattle was the center of the music universe in the early 1990s. The scene led to maybe the most profound paradigm shift in mainstream rock and roll since the British invasion of the 1960s. Having the words "Seattle band" come before your name could almost guarantee you a record deal. Bands from the scene (most famously Soundgarden, Pearl Jam and Nirvana, but also groups like TAD, Screaming Trees, and the Melvins) repurposed the fury of punk and combined it with the groove of heavy metal to create something new and seemingly vital and, for a short time at least, filling a much-needed void. The musicians were snarly girls with dreadlocks and nose rings and angry guys with stringy hair and goatees. They wore flannel, Converses and torn T-shirts, and they uniformly rejected the lip-gloss-and-leather-pants excess of 1980s cock rock. Bands like Poison and Warrant and Nelson and Winger spasmodically went the way of the Dodo. Earnestness and "authenticity" were fashionable again.

And then it all fell apart.

Two violent events, occurring within about a year of each other, brought about the near immediate death of the scene. The first was the brutal rape and murder of Mia Zapata, lead singer of The Gits, in 1993. The second was the suicide by shotgun of Kurt Cobain, the closest Generation X had to a genuine John Lennon figure.

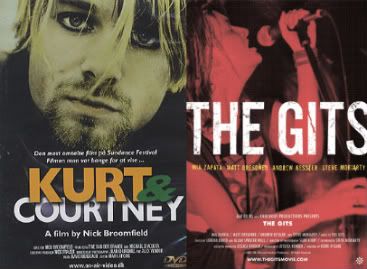

A pair of critically acclaimed documentaries chronicle these two events. Nick Broomfield's Kurt & Courtney came out in 1998, when the wounds were still pretty raw. Kerri O'Kane's The Gits appeared in 2005, long after the dust had settled.

The Gits is a pretty standard rockumentary tribute to Zapata, combining archival concert footage, photos, and talking heads spouting platitudes about how influential the band was and how amazing a person and singer she was. It's too bad the movie isn't more adventurous, because the subject matter is fascinating. The Gits were one of Seattle's best undiscovered gems, right on the verge of cracking the mainstream, when Zapata was killed. They were a pretty straight-forward hardcore punk band and weren't really part of the adjacent (and largely rival) grunge scene. Zapata's skill as a singer was truly astonishing. She was sort of a snarlier and bluesier Patti Smith, and her powerhouse talent and her generous support of the bands that came in her wake helped give birth to the Riot Grrrl movement (which included celebrated girl punk bands like L7, Bikini Kill, and the direct Gits-disciples 7 Year Bitch).

The first half of the documentary follows the band's rise, from their early days at Antioch College in Ohio to their dominance of Seattle's punk scene. Her former band members expound on Zapata's brilliance, and the musicians from the other scene bands like 7 Year Bitch and DC Beggars talk at length about her influence. It's all fairly banal stuff, with a few amusing anecdotes thrown in (the most charming moment is a clever montage of her various friends lovingly impersonating her gravelly voice). But it's the concert footage that shows the truth of her abilities. I'm sorry, but the woman could sing.

The story takes it's unfortunate turn at Zapata's murder. Zapata was walking home from a bar after spending the night hanging out with members of 7 Year Bitch when she was accosted, beaten, raped, and strangled. The police searched for nearly a decade for the killer, operating on the assumption that it had to have been somebody she knew. Men from all over the punk scene were interrogated, and the women walked around in fear, not knowing if the killer moved amongst them. The camaraderie of the scene was shattered, and -- as one interviewee said -- almost all the bands broke up within a year of her death. The magic, as they say, was gone.

I wanted O'Kane to really dig into the psychology of that dark time, but -- as is the case in the first half of the film -- she's content to just skip over the surface. The only real emotion we see is from Zapata's father (who seems like the best and most loving dad a hardcore punk girl from Kentucky could ask for) and from 7 Year Bitch singer Selene Vigil, who -- years after the tragedy -- seems still shaken by the death of her friend and mentor. But O'Kane just keeps pumping out the platitudes about how awesome Zapata was, and after awhile you're left with the sense that she must have been the Mother Teresa of Seattle's punk scene. No one has a single unkind or complicating thing to say ab out her. I'm sure she was as lovely a person as everyone says she was, but O'Kane never really finds a way to humanize her. She leaves her as a martyr and an idol, not a person.

There's a happy ending, of sorts, when the police finally make an arrest using DNA evidence 10 years after her murder, but the impact of that final turn is muted by the fact that O'Kane never really brings home the pain of her loss.

Still, with all its flaws, The Gits is worth a watch if you have even a passing interest in the subject. As I said, the concert footage alone is worth it.

Nick Broomfield's Kurt & Courtney is the much more stylish film. Broomfield has a much stronger sense of cinematic language, and he largely eschews the conventions of the talking-head documentary. He moves the camera, for one thing, and rather than just showing us the interviews he gives us all the awkwardness of the first meetings and introductions (my favorite is Kurt Cobain's old high school teacher, who yells at the filmmakers as if they're tardy students before finally settling down and agreeing to the interview). This gives the film a lived in, organic feel and adds to the sense of verisimilitude ... which is important considering that Broomfield's film is less a tribute and more a piece of conspiracy-theory agitprop.

"I didn't have an angle on the story," Broomfield says in what has to be one of the most stupendously disingenuous statements in the history of documentary filmmaking. "I was just trying to find my way through it." Yeah. Right. I call bullshit on that one.

Broomfield is an excellent craftsman and he knows how to structure a narrative. In Kurt * Courtney he tells three stories simultaneously: that of Kurt Cobain's rise and fall, that of the Courtney Love's alleged involvement in his death, and that of himself -- the poor camera-wielding David versus the Goliath that is Courtney Love and the Hollywood media machine -- battling to get his film made.

Broomfield's main thesis (although he denies it) is that Courtney Love had Kurt Cobain killed to protect her financial and professional interests. To prove his point, he travels the country (okay, the West Coast) and interviews a bunch of crackpots and junkies, each of whom has his or her own story to tell. The most fascinating are Cobain's clearly drugged-out best friend (who may have been in on the plot, Broomfield slyly suggests), Courtney Love's estranged father (who is convinced she had him killed and is apparently making as much money as he can off the accusations), and -- of course -- Eldon Hoke, otherwise known as "El Duce." Hoke was the lead singer of the notorious "rape rock" band The Mentors (they made GWAR look like a Disney attraction), and he claimed that Love offered him $50,000 to kill Cobain. He lived a squalid, hillbilly existence out in Riverside, CA, and at the time of his interview he looked to be about 39 going on 60. It's not hard to believe this guy could have killed someone, even if his story stinks like a rotting fish in the noon sun. At one point Broomfield asks Hoke how Love had suggested he commit the deed. "Blow his fucking head off!" Hoke shouts, clearly giddy at the idea. "That's the way it's done!"

Interestingly, Hoke was struck and killed by a train just a few days after his interview, which of course threw a whole mess of gasoline on the already raging conspiracy-theory fire.

To be fair to Broomfield, he doesn't really try to convince us that these people are anything but crackpots and junkies, and he gets a lot of narrative mileage out of the growing uncertainty surrounding his quest. "I no longer knew whether anything anyone was telling me was true," he says at one point, and you can just about hear the thunderclap going off on the soundtrack. The only person who seems unquestionably honest is Cobain's beloved aunt Mary, an ever-smiling and hyper religious woman who seems so homespun and saintly as to be almost creepy. I wondered if maybe she had wandered in from a forgotten episode of Twin Peaks.

Broomfield is cut from the same cinematic cloth as fellow agitprop documentarians Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock, and he knows the benefit of having a good villain. When Broomfield finally confronts Love at a swanky ACLU dinner in Los Angeles, it's impossible not to think of Moore raging at GM chairman Roger Smith at the end of Roger & Me. Like most of Moore's movies, this film is shamelessly manipulative, embarrassingly narcissistic ... and pretty damn effective. By never outright stating that he thinks Love killed Cobain and by allowing himself to (on camera, at least) question the veracity of the evidence like a true journalist, he manages to create a pretty convincing argument that, at the very least, the question itself isn't completely insane. He uncovers enough genuinely weird stuff to make one wonder.

And, whether or not she actually had Cobain killed, Love is unquestionably the villain of this movie. Broomfield's idea seems to be that, at the very least, she probably drove him to suicide (another former lover of hers pretty much says as much). No one is going to walk away from this movie mistaking her for a nice person.

Whether or not you believe the conspiracy theories, Broomfield's documentary is pretty interesting and, in its way, genuinely thought provoking. But, please, take it with a grain of salt.