NOTE: SOME MILD SPOILERS AHEAD

I love all types of horror movies. Monster movies (anything from Tremors to In the Mouth of Madness to Night of the Living Dead), ghost movies, alien movies (The Thing, They Live), evil-kid movies (Joshua), demonic possession movies, freaky drugged-out mind-fuck movies (Jacob's Ladder), plus all combinations thereof (Event Horizon). I can even appreciate a good slasher film, if done right (The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is still the gold standard, as far as I am concerned).

What unites all these films -- indeed, what unites almost the entire genre -- is the basic activity of watching a person or a group of people being forced to confront some seemingly unstoppable and inexplicable outside force. It's all about the fear of "the other," whatever that other may be. H.P. Lovecraft took this notion to its furthest extreme with his tales or cosmic horror, where the human characters find themselves so completely overwhelmed by their encounters with impossibly powerful and completely unfathomable Godlike entities like Cthulhu, Dagon, The Goat With The Thousand Young, etc., that they are rendered completely useless and are -- almost to the man (Lovecraft didn't write a lot about women) -- driven to madness.

Literary and film critics have tried time and time again to quantify this "other" in psychological terms, to make the monsters, ghosts, demons and serial killers stand for something recognizably human and -- too often -- mundane. Sometimes the conclusions are obvious. Frankenstein's monster represents our fear of scientific progress. The slasher killers of the 80s are stand-ins for AIDS. Sometimes the connotations are ugly and uncomfortable. Vampires become our rape fantasies. King Kong is about the White Europeans fear of the Black African (and, after seeing Peter Jackson's portrayal of the ochre-painted natives in his massive-budget remake, I have to say I can see the point). Sometimes they seem more than a little ludicrous. I remember reading an article that drew a line from old tentacle-faced Cthulhu Him(?)self to Lovecraft's supposed pathological terror of his mother's vagina.

There may be something to all this, even if the arguments can become a bit reductive. What ultimately matters -- I think -- is that there is some part of our unevolved, reptilian brains that is still afraid of the dark...and whatever might be lurking within it. This "whatever" can take on any form it likes. It can be Hannibal Lecter, the creepy-voiced Pazuzu from The Exorcist, fire-breathing Godzilla, the weird ghost hand pressing against the door in The Haunting. All we know for sure is that IT IS NOT US.

There's a reason why Stephen King named his novel about the shape-shifting clown It.

This kind of horror -- which I'd ballpark guess makes up 90 percent or more of the genre -- is ultimately comforting. By making the evil something that exists completely separate from ourselves, these stories reaffirm our humanity. And by turning our rape fantasies into Dracula or our Freudian vaginal disgust into Cthulhu, we're given enough distance to tell ourselves that it's only a story, and we don't have to take it seriously if we don't want to.

This is not an original observation, by any means. But I think it's basically a true one.

There is another kind of horror story, however, one that is at once simpler, bleaker, more nihilistic, and -- I believe -- much scarier. These are stories that take us into those weird little places that lurk just a hair's breadth beyond the reach of civilization, where the comforting veneer of modernity that we depend on to get us through our day is suddenly torn away and we're confronted with the fact that -- at the end of it all -- we're basically still animals. In these stories, our own capacity for violence is limited only by our imagination.

Call it the Lord of the Flies school of horror. The movies don't seem to take us there too often, or at least not directly. If a film treads into those waters, it's more likely to be couched within some sort of crime-based revenge fantasy (like Deathwish or its Kevin-Bacon-starring offspring Death Sentence), an Apocalyptic future (A Boy and His Dog), or a distant war scenario (Apocalypse Now). Occasionally someone will take a crack at a really serious drama (Straw Dogs) or even a black, black comedy (Very Bad Things, or just about anything by the Coen Brothers).

Horror movies themselves don't seem go there too often (although you do see much more of it in horror fiction...anyone who's ever read a Jack Ketchum novel knows what I'm talking about). There are a few exceptions, like some of Wes Craven's early work (Last House on the Left, The Hills Have Eyes), but those tend to be pretty few and far between. I think this is probably because -- at least in our country -- studios are simply afraid to go there. It's much easier to sell an unapologetically scary movie if you at least provide the dubious comfort of some external source of all the carnage. Even most of the newish wave of "torture porn" films tend to give us a clear and distinctly separate antagonist (I don't know about you guys, but I've never met anyone who resembles Jigsaw from the Saw films). It's simply harder to get a studio to sign onto something that just goes ahead and rips the scab off the wound and says, in effect, that we're the problem.

I'm guessing most of you know what a "donkey punch" is, but I'm gonna go ahead and describe it anyway so that there's no confusion. If you're squeamish about such things, skip the rest of this paragraph (and for God's sake, don't see this movie). A donkey punch is a gross, irredeemably misogynistic, mostly apocryphal don't-try-this-at-home sex act wherein a man, whilst performing anal sex on a (likely female) partner, delivers a vicious punch to the back of the head right at the point of orgasm, thereby causing an involuntary contraction of the partner's sphincter muscles and, in theory, increasing exponentially the level of pleasure during climax (for the puncher, of course, not for the punchee).

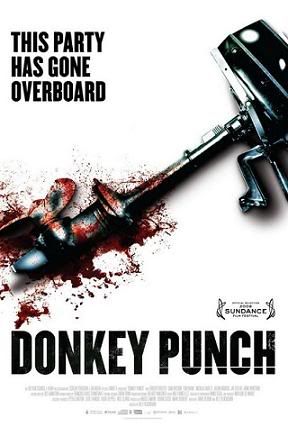

Donkey Punch -- the movie, not the sex act -- is the first film from English music-video director Oliver Blackburn (who co-wrote the script with David Bloom). Set in coastal Spain, it opens with three vacationing lasses from Leeds (Sian Breckin, Jaime Winstone, and Nichola Burley), who encounter four caddish but charming enough Londoners (Tom Burke, Julian Morris, Robert Boulter, and Jay Taylor). The boys crew a luxury yacht, and they invite the girls onto the boat to party. The girls go (of course), and before long are all stripping down to their bikinis. The alcohol and ecstasy are supplemented by crack, and the conversation turns -- as it so often does in these situations -- to sex. There are brief discussions of the "dirty sanchez," the "rusty trombone," and -- of course -- the donkey punch.

Finally (and inevitably) two of the girls go down below with two of the boys. A third boy accompanies them, video camera in tow. The two "nice" kids stay up top and talk about, you know, feelings and relationships and stuff, while the others rip off each others' clothes and engage in the type of spontaneous on-camera orgy that you see popping up in online porn every so often (and, no, don't ask me how I know that). The boys egg each other on. Finally, one of them tries a donkey punch. And a girl ends up dead.

So there's your setup. The best one-sentence description I've read so far comes from Scott Tobias of the Onion A.V. Club, who wrote: "...the film is what Dead Calm or Knife In The Water would look like if they featured late-period cast members from The Real World." If you think it all sounds tawdry, you're right. I'm generally a pretty unflappable movie-goer, but I'm not ashamed to admit that I watched the orgy scene in particular with my mouth agape and consumed by the itchy feeling that I needed a shower.

What sets Donkey Punch apart from its hardcore horror contemporaries and elevates it somewhat beyond the limits of the Howard-Stern worthy premise is Blackburn and Bloom's eye for moral ambiguity. The characters are fairly generic on the page. The girls fall into two types: Tammi (Burley) is the shy and reluctant one, while the other two are apparently up for just about anything. The boys are equally archetypal. You have Sean (Boulter), who -- on the surface, at least -- comes off as responsible and sensitive. On the other end of the spectrum is the thuggish and amoral Bluey (Burke), who provides the drugs, steers the conversation to rough sex, and eventually engineers the on-camera orgy. In between the two extremes are Marcus (Taylor), the ship's arrogant skipper; and Josh (Morris), Sean's boyish and unfortunately suggestible younger brother.

These are not complicated characters, but Blackburn is a smart director and he and his actors have an impressively clear eye for nuance. They avoid packing in a lot of backstory and instead look for the little moments -- a lilt in one's voice, a twitch in the eye, a particularly revealing turn of phrase -- to establish the characters. They infuse the performances with an easy naturalism that makes these kids relateable, if not entirely likeable.

This is key, because when the shit goes down and eveyone inevitably turns on everyone else, the situation remains horrifyingly plausible.

The film could have very easily been another us vs. them horror movie, with the boys being the obvious villains. But Blackburn's not interested in that. No one in this film is a monster...or, at least, no one is any more monstrous than anyone else. At first the boys -- fearing for their jobs and their freedom -- make the executive decision to dump the body and concoct a believable cover story. They repeatedly try to convince, cajole, and eventually bully the surviving girls into going along. The girls resist. And I think you can guess where that's going to lead.

Most of the characters (except for the dead girl) commit at least one truly nasty act of violence, and they are each given a plausible motivation for his or her behavior. The violence -- when it comes -- is more the result of fear, frustration, and a few remarkably bad choices than any inherent psychopathy on anyone's part. Bluey would seem to be the obvious choice to fill the villain role, but Blackburn and Bloom sidestep this pitfall nicely by never making him directly responsible for any of the violence. He's a thug, sure, but he's mostly shit-talk and bluster.

Blackburn and Bloom craft a superbly realized thriller by relying on this crazy-kilter seesawing of the audience's sympathies. As soon as you think you've pinned down the villain, someone else does something worse.

There are some serious missteps, however. Blackburn and Bloom stage a conversation over a loaf of bread just after the body has been dumped that is filled with tension and a nauseating sense of dread, but they end up pushing it way too far in a desperate attempt to bridge a narrative gap and nearly blow all the credibility they had earned over the previous hour or so.

In retrospect, that beat was portentious because the movie -- so carefully constructed in its first two acts -- descends into familiar stalker/slasher territory during the last twenty minutes. Blackburn and Bloom toss aside the meticulous interior logic they had spent so much time lovingly creating for the sake of simple narrative expediency. Characters start behaving in ways that people only do in movies...which would be sort of forgivable if the filmmakers hadn't done such a solid job of defying the genre conventions in the movie's early stages.

But in a world overstuffed with crap like the upcoming Saw VI and the unforgivable remake of The Stepfather, I'll take a hard-hitting and thematically ambitious movie like Donkey Punch any day. It manages to be a pretty taut, engaging, and genuinely thought-provoking psychological thriller, and even if it ultimately falls short of the high bar it sets for itself I have to give everyone involved credit for going for it.

No comments:

Post a Comment