Hey, guys. I hope you'll indulge me a little bit here.

My grandfather, Edwin Houston Harrison, passed away last night at the age of 102.

I kind of wanted to say a few things about him. Okay, a lot of things. This is sort of a weird venue, I guess, but it's the only one I have. So here goes.

Like most people, I imagine, I didn't really know that much about my grampa when I was a kid. He had lived several lifetimes before I was a speck on anyone's horizon. By the time I came along he was retired and motoring around the country with my grandma in their old silver pickup truck and travel trailer. The earliest memory I have of him is being up at Vallecito Lake outside of Durango, Colorado. He was talking to my brother (who was probably 13 or 14 at the time; I might have been two or three) while loading fishing poles into the back of the truck. I didn't even really know what the poles were for, but I knew it had something to do with fish and I remember being really mad because I couldn't go with them.

My grampa was the strong and silent type. Grandma was as vivacious and bubbly as could be. She talked a mile a minute, usually at top volume, and she had an infectious laugh that rolled out of her like the tide. So Grampa probably just figured he'd let her do most of the talking and keep himself to himself.

Consequently, I never really heard all that much about him or what had gone on in his life before I showed up. I knew he had been born on a farm in Oklahoma, and that his first wife had died shortly after giving birth to my Uncle Eddie in the 1930s, and that somehow he and my grandma had ended up in Los Alamos during WWII and that he had something to do with building the roads.

That was about it. To me he was just my grampa.

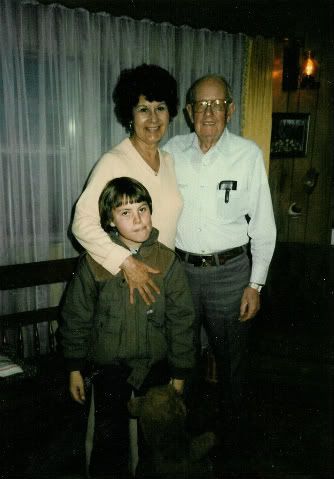

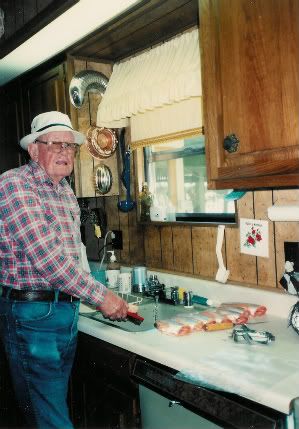

I don't know why I'm making that face

He was 16 years older than my grandma, so when she passed away back in 2006 I think he was more shocked than anybody. That was the first and last time I ever saw my grandpa cry. It was also, incidentally, the only time I remember him telling me that he loved me. I didn't mind. He wasn't a demonstrative guy, and I guess it had always been understood.

After Grandma died I decided I wanted to get to know Grampa a little better. So I borrowed a camera from a friend and I recorded about seven hours of interviews with him about his life.

Grampa's earliest memory, he told me, was living in a half-dugout on his parents' farm outside of Olustee, Oklahoma. His dad was a homesteader. They had 160 acres that they had to make workable ("proved up," as my grampa said) before they could own it outright. In the meantime, they lived in a one-room cabin, half dug out of the ground, with wooden planks for walls, thatch for a roof, and blankets and old newspaper for insulation.

One winter, when my grampa was about two, they had a nasty blizzard and his dad had to bring the chickens and one of their calves into the dugout so they wouldn't freeze to death. Grampa -- who was about 98 at the time he told me the story -- said he clearly remembered the icicles hanging from the calf's eyelashes.

That's him on the right.

Grampa was the oldest of nine kids (all but his youngest sister Johnny have passed away). He had the misfortune of trying to go into farming himself just as the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression hit. He married his high school sweetheart, Verna, rented a tractor and a plot of land south of Olustee, and got to work.

But it was no good.

"I made good crops down there, but you just couldn’t sell them," he told me. "I sold cotton for six cents a pound and wheat for 31 cents a bushel. That doesn’t even pay to harvest it. I had to give that up.”

in 1933 Verna gave birth to one son, Jimmy Dean, who died at birth. My uncle Eddie was born in 1936. The (possibly apocryphal) story my grandma told me when I was a kid was that two weeks after the baby was born Grampa went into town to buy her a pair of slippers. He came back to find her dead, probably of a blood clot.

I tried to ask Grampa about that when I interviewed him. He just grimaced a little and said "I don't really want to talk about that." So we moved on.

The farm went belly up, and Grampa bounced around for a long time looking for work. His family took in Eddie while he was out on the road. He started with construction in Oklahoma, mostly on roads, and before long this took him all over the Southwest doing contracts, mostly for the military, as the country geared up to enter WWII. He worked in Roswell for awhile, and El Paso, and in 1940 he found himself in Gallup building concrete "igloos" for the armory.

One day, during his lunch break, he met a pretty young waitress at the local Greek restaurant named Paula "Polly" Gonzales. She was 18. He was 34.

Grandma and Grampa both told me the story of their meeting about a year or so before she died. Unfortunately this was before I had the idea to put this stuff on film, so I don't remember all the details. The one thing I do remember was thinking that it sure sounded like he was dating someone else at the time. Grandma called this mysterious other woman his "friend".

When I pressed them on it, they just kind of gave each other a sly little look and laughed.

At any rate, they were married a few short months later on December 9, 1941, two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Grandma and Grampa with my Uncle Ron

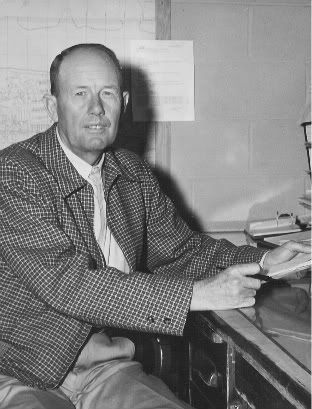

And years later

My Uncle Ron was born in Gallup. The three of them moved around for awhile, landing again in Roswell, then moving onto Hobbs, Ft. Sumter, back to Oklahoma. They were living in Albuquerque when a friend of his from his time in El Paso told him about a mysterious new government job up in a place north of Santa Fe.

There wasn't a lot of housing up in Los Alamos at the time, so Grampa went into a bank in Santa Fe and got a loan for $1,500 to buy a travel trailer. They towed it up the hill in their Buick sedan, and they lived in that trailer for several years.

Grampa was one of the first eleven civilians to work in Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project. He started in the auto pool as a mechanic.

I asked him what he thought the Trinity test and Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Did he have any inkling of what was brewing up there?

He didn't seem to understand the question. "Didn't think anything of it," he said. "We all just did our jobs."

Los Alamos ended up being the place where they would stay. After the war my Grandma gave birth to my mom (they were still living in the trailer at the time). They sent for Uncle Eddie, got themselves a house, and Grampa started working with the Zia Company building the roads all throughout town. He retired in 1973 as Superintendent of Roads, Labor and Mechanics.

Once retired, he and Grandma bought themselves another travel trailer and hit the road for about fifteen years or so. I came along in 1977. By then they had pretty much decided that Vallecito Lake was their favorite spot, and in the mid 1980s they sold the travel trailer, bought a mobile home in a little retirement community near the lake, and settled there permanently.

I've never talked to my brother or my cousins about this, but I would hazard a guess that my experience with my grandparents was very different from theirs. I'm the youngest. They're all sort of clumped together in age, and I was a late comer by about a decade. Grandma and Grandpa were traveling a lot when they were kids, and since there were so many of them they had to share.

By the time I wasn't still peeing my pants or eating the Play-Doh, they were pretty much settled in Colorado. I sort of had them to myself.

Yep, that's me again

I used to go up there for a few weeks every summer, either with my parents or by myself. I remember how cool it was, even in July, surrounded by all those pine trees. I remember the sound of the birds, always there, and how I used to sleep out on their covered porch and lay awake at night and watch for raccoons.

My grandma used to take me to Bingo with her once a week down at the little community center in the trailer park. I won $5 once. I think that was the happiest moment of my life up to that point.

I remember that they used to have a drag show once a year, believe it or not. I only saw it once, I think. All the old timers would borrow their wives' dresses and scarves and gloves, throw on a wig and put on stockings and rouge and ruby red lipstick, and then go strutting their stuff on the catwalk. The old ladies would hoot and holler and throw things and generally laugh themselves silly.

When my grampa came out from the back, wearing a purple dress and a long blond wig and two bright dangly clip-on earings, my eyes were the size of cookie tins and my jaw hung wide and loose like a trap door. This was my grampa, after all. A man's man through and through. I knew he was supposed to be part of the show, but I don't think I believed it until I saw it.

Grampa saw me sitting there in my grandma's lap, my face agog and full of naked wonder, and he smiled a crooked little smile that let me in on the joke. "Can you believe I'm up here in this ridiculous get up?" that smile seemed to say.

And then he tipped me a wink. I just about died of laughter.

Mostly, though, I remember the fishing.

Yep, I finally made it out there on the lake with him. By this point my brother was off at college or maybe living in Albuquerque, so it was usually just the two of us. He'd wake me up unceremoniously well before dawn. I'd groan, then smell the eggs or the toast that my grandma had made for me, pull myself out of bed, wipe the sleep from my eyes, and stumble into the kitchen to have a mostly silent breakfast with the two of them. Then my grampa would say something like "best get to it now," and my grandma would give me a thermos with hot chocolate when I was younger, coffee when I got a little older, and a plastic baggie full of her homemade chocolate chip cookies (the best I've ever had, let me tell you) and banana bread.

Then I'd pull on my shoes and trudge out after him to that old silver truck and we'd drive the couple miles or so down to the lake, neither of us talking much but Grampa occasionally singing a little bit under his breath. I'd sit next to him and yawn happily and watch as the sun started to peek its head up over the rim of the mountains.

We would get to the wharf, and Grampa would josh a little with the guys there, and one of them (usually a kid) would go out there and tow his boat back to the dock. We'd climb in, and I'd always be a little bit scared when I'd put my foot onto the bottom of the boat and feel it rock a little on the water. But Grampa always put a thick hand on my shoulder to steady me, so that was all right.

Then we'd charge out to the middle of the lake, and when he decided we were far enough out we'd let our lines out. I'd stare at the reel as the line unspooled into the water, making a soft and reassuring whir-whir-whir sound as it went. It was lead line, color coded by the number of feet. First blue, then red. When it would get to the yellow I'd thumb the catch and it would stop.

Grampa would shut off the motor and we'd sit there waiting. And waiting. And waiting. He always let me sit up at the front of the boat, so I'd lean back in my seat and put my feet up on the middle bench and just watch the line as it twitched a little, teased by a twig or maybe a slow current under the glasslike surface that I couldn't see.

After awhile, Grampa might start singing a little. I usually couldn't understand what he was saying. His Okie accent was so thick as to be almost a caricature, and whenever he sang he'd exaggerate it a little. But I loved the sound of his voice.

Sometimes we'd talk a little bit. He'd tell me about the different kinds of fish: Coconi salmon, rainbow, brown trout, the occasional pike near the shore that could cut your line with their sharp little teeth. He'd tell me how the fish got there, and how he knew what part of the lake to go to each morning to get the maximum number of bites.

Sometimes he'd tell me stories. I think it was out there on the lake when he first told me about Monkeyjack and Rawhide and Bloody Bones -- who came to snatch little boys out of their beds when they're bad -- thereby scaring the bejeezus out of me but also probably inadvertently helping spur my lifelong love of monster stories.

One day he taught me how to yodel. There was no one else out there, so there was nobody we could bother. We sat there, shouting "yodel-i-oh-i-oh" at the mountains, daring each other with each yell to be just a little bit louder...a little bit louder...and hearing our voices rocket back at us across the water. I remember thinking it was kind of like magic.

Then we'd get a bite. "Heyup!" Grampa would say, and I'd bounce up and down in my seat, full of excitement and always for the first few seconds not quite remembering what to do, and then I'd grab my pole and start to reel in. Grampa would coach me, tell me to ease up when I needed to and let that sucker think he was gonna get away, tell me when to pull and when to let him swim. I'd watch the line change from yellow to red and finally back to blue, and then the clear leader would emerge with the shiny spinning lures (Grampa called them "twizzlers"), and after that, by golly, there'd be a daggum fish!

"There it is!" I'd shout, and Grampa would grab the net and I'd try with all my might to fight that thing up to the surface. Sometimes the fish would get away. But usually not. Usually Grampa would just scoop it up and drop it to the floor of the boat, and we'd watch it flop around there for a bit before throwing it into the cooler. Then Grampa would fix my bait and fire up the engine, and we'd let the line out and do it all over again.

Let me tell you one of life's great secrets: Nothing tastes better than a fresh fish you pulled out of the water yourself.

Eventually, as the years went on, it got harder and harder for them to stay up in Colorado. The closest hospital was over in Bayfield, which was twenty minutes away. Grampa fell off the roof one winter while clearing snow and banged himself up pretty good. He wasn't seriously hurt, but I think that was what convinced him and it wasn't too long after that they decided to sell the trailer and head back to Los Alamos. My Mom and Uncle Ron bought a little house for them.

Without a lake nearby, he was pretty much done with fishing. So he took to doing work on the house instead. He was in his late 80s or early 90s when he built the back patio, mostly by himself (Uncle Ron and my cousin Kenny helped with the roof). He was losing a lot of his strength by then, so he devised a system of pulleys and levers to help lift and move things. That still blows my mind.

After the patio was done he got to work on his garden. He was in his mid 90s, I think, when he really tackled it in earnest. When we were preparing his 100th birthday party two years ago, I put together a little video slideshow to show to the guests. The only picture he cared about was this one:

That's the patio he built

When my Grandma died, it was a shock to all of us. She had been in great health, still walked a mile every day, and seemed to be bouncing back nicely after surgery on her knee.

This is the story that I remember hearing. I might not have all the details right, but I think I got the gyst.

Early one morning, while it was still dark, Grandma woke complaining of a strange pain and a feeling of heat in her shoulders. She and Grampa discussed what they should do, whether they should call the ambulance or maybe call my Mom to take her to the hospital. But they decided they didn't want to bother anyone. Grandma drank a ginger ale, thinking that would make her feel better, and they went back to bed.

When my Grampa woke up later, Grandma was in the bathroom. Grampa went into the kitchen, fixed himself something to eat, and talked to my Uncle Ron (who was by then living in St. George, Utah) on the phone for a bit. After getting off the phone it occurred to him that Grandma had been in the bathroom for an awful long time.

He went to check on her and found her slumped against the door, blocking it so that he couldn't get it open.

He called my mom, said something to the effect of: "Your mama fell down in the bathroom and I think she's dead."

I was interning at LionsGate in Los Angeles at the time. My dad called me and told me what happened, that my Grandma Polly had passed away. It sounded like a heart attack. This didn't seem possible; before I left two months earlier she had seemed as bubbly and vivacious as ever. I immediately booked a flight home.

When I made it up to my grandparents' house the whole family was there. Grampa came into the living room from kitchen, tottering on his increasingly unstable legs. His eyes and cheeks were wet with tears.

"How're you doing, Grampa?" I asked. I had no idea what else to say.

"Not too good, Scott," he said, and he grasped my hand and squeezed as hard as he could. His voice was thick and shaky. "Not too good at all."

We sat there for awhile, all of us, numb, not talking about much in particular.

Finally, as I was getting ready to go, I went to him and put my arms around him and kissed him on the forehead. "Bye, Grampa," I said.

"Bye, Scott," he said. Then: "I love you."

After Grandma was gone, the burden of caring for him for the next few years fell mostly to my mother and my cousin Kenny. Grampa insisted on staying in his house and -- for a guy edging out of his 90s -- did remarkably well for himself. But he was getting weak, and none of us trusted his legs.

Eventually Kenny moved in with him and helped care for him. I have to say, I think my cousin acquitted himself heroically. I don't know if I could have done it.

Grampa continued to get weaker and weaker, and before long he wasn't able to do much with his garden. So he mostly sat and watched sports (on mute, because he didn't give a wit what the announcers had to say, he could follow it just fine, thank you very much), did his crosswords, and listened to his religious shows on the radio. It was during this time I got it in my head to interview him on camera.

Finally, about a year ago, he went to live with my aunt and uncle in Utah. Kenny was preparing to get married, and it was getting too hard for my mom to be there all the time without living with him.

After Grampa left, I didn't talk to him much. He was almost impossible to understand on the phone, for one thing. But, to be honest, I just didn't really know what to say.

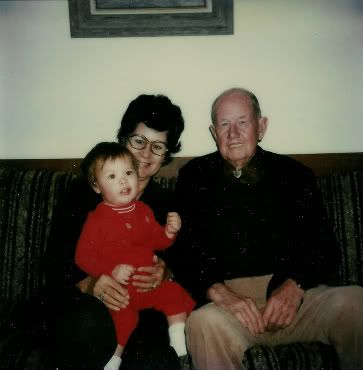

Grampa with my mom on his 102nd birthday in Utah

About a month ago he developed pneumonia. He had had a lot of trouble breathing for years, and at his age the strain was just too much. His throat was full of phlegm and he could hardly swallow, so it became next to impossible for him to eat. My mom told me about the only thing he could keep down was one bottle of Ensure a day.

My mom and I talked to him on the phone this past Sunday.

"How're you doing, Grampa?" I asked.

"Not too good, Scott," was the reply.

As always, it was hard to understand him. But we talked for a bit, and he was delighted to hear that I got a job teaching. He wished me luck.

"Take care of yourself, Grampa," I said when we signed off. I didn't understand what he said in return.

That was the last time I talked to him.

It was only later that I realized what I forgot to say. So I'm going to say it now.

I love you, Grampa.

I hope you're well wherever you are, and that there are plenty of fish to catch and flowers to tend to.

I love you.

And I miss you.

Goodbye.

8 comments:

I'm sorry for your loss Scotty; this was a very lovely tribute to a remarkable man.

that was beautiful Scotty....

you're Grampa is diggin' that great swirlie networking site in the sky and he is really in love with you....

and i heartily concur

thanks daddy

xoxox

Oh, Scotty! I'm glad you interviewed him. What a life!

Scottie,

Thank you for sharing a bit of your Grampa. I am sorry for your loss.

I miss my grandmas all the time.

It's amazing that you documented those interviews with him--precious & invaluable.

Sarah.

Hey, Scotty, that was beautiful. Thank you.

Ben

He was wonderful and you are wonderful. Thank you for this.

this is a beautiful tribute, scotty. i'm sorry for your loss.

Post a Comment